Plastic is not only a huge problem for our environment, but has also been suspected for years to be harmful to our health – with more and more studies proving this.

And yet:

We drink from plastic bottles and store our food in plastic containers or plastic wraps. We live in rooms that are furnished with floor coverings, wallpapers or wall colors made of plastics.

Phones, charging cables, steering wheels, drinking bottles, cups, keyboards – almost everything we touch is made of plastic.

It is indisputable that we are surrounded by plastic and that we regularly absorb it into our body via our food, skin and the air we breathe.

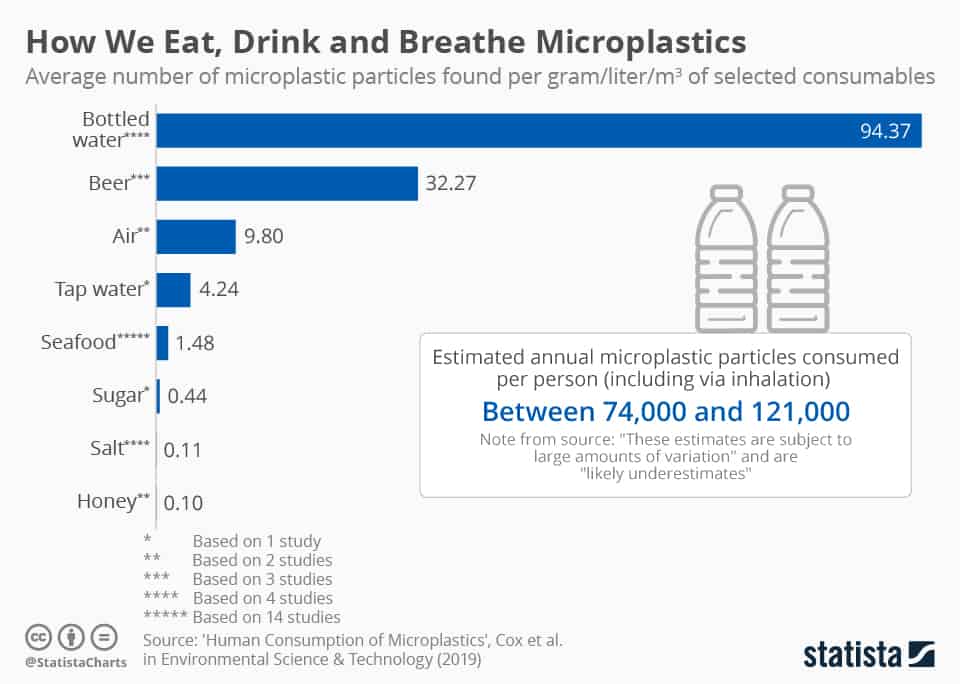

In addition to the visible plastics that we come in contact with, there’s the growing issue of microplastics (plastics that have broken down into tiny fragments):

In this post, we’ll take an honest look at how great the danger of plastics really is, what science and study facts have to say about it, and what type of plastics you should avoid.

You will also get a bunch of really useful tips that help you in everyday life to protect your health and the environment.

Sounds good? Cool. Let’s dive right in.

What makes plastic unhealthy or dangerous?

There are certain types of plastic that are approved for use in food and pharmaceutical industries because they are considered to be harmless to human health (for example, polypropylene).

On the other hand, it is a well-established fact by now that polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is extremely toxic to humans and the environment.

As you can see, plastic cannot be lumped together – it depends on which kind of plastic we are talking about. In fact, often it is not even the plastic itself that is the main issue – the additives are often the harmful substances.

Volatile additives pose hazards

Plasticizers, UV stabilizers, flame retardants, and various other added chemicals are used to give the plastic the desired properties.

The problem is that these additives are often not permanently chemically bonded to the plastic. Instead, they leach out into the environment, our skin and food.

Often, the additives simply evaporate into the ambient air which we inhale.

There are plastics that contain more, less (or even none at all) of these questionable additives.

Let’s take a look at some substances that are considered to be harmful and which have been studied and researched for a long time and their effects are thus well-known.

Plasticizers – Phthalates & others

Plasticizers are used to make initially hard and brittle plastic elastic and soft. That way, they often make the product usable in the first place. Unflexible rubber boots or hard air mattresses would probably not be very popular with the consumers.

By far the most common group of plasticizers are esters of the phthalic acid – also called phthalates. In Western Europe alone, 1 million metric tonnes of phthalates are produced each year.

However, there is no such thing as “the one” plasticizer, but a whole range of chemicals that are used for this purpose. Some of them are more harmful to our health and the environment than others.

90% of plasticizers are used in PVC products, e.g. plastic foils, wallpapers, floor coverings, tubes, pipes, cables, and many more. Other candidates that may contain plasticizers are:

- Soft children’s toys

- Airbeds

- Rubber boots

- Glues and adhesives

- Paints

- Varnishes

- etc.

How can you tell whether or not a product may contain plasticizers? Fret not! We’ll get to it in a minute.

How dangerous are phthalates?

Many phthalate compounds are considered harmful to health and are suspected to cause:

For this reason, quite a few members of the phthalates family are on the list of “substances of very high concern” in the European Union, including the phthalates DEHP, DBP, and BBP.

DEHP for example used to be the most widely-used plasticizer among phthalates until recently. But since its reproductive-damaging effects became public knowledge, politicians were forced to act – and banned the use of DEHP in certain products – e.g. in children’s toys and baby items.

However, in many other products, its use is still permitted – although in some cases legislation requires compliance with certain permissible threshold values.

Problematic substitute plasticizers

Since the prohibition of DEHP in certain products, the chemical industry has replaced DEHP with substitute plasticizers such as DINP and DIDP. These two substitute phthalates have now become the most widely used phthalates in Western Europe. They are considered to be “less toxicologically questionable”.

In fact, these substitutes are far from harmless (and indeed chemically very similar to DEHP). For example, DINP and DIDP are suspected to have liver-damaging effects, which has already been demonstrated in animal experiments.

Also, another concern is gaining momentum:

Currently, the EU’s threshold values and risk assessments always only apply to isolated chemicals (as do virtually all legislators worldwide).

This flies in the face of increasing scientific evidence which proves that the absorption of several chemicals can be more harmful than the sum of the individual substances’ effects.

Therefore, the interaction of chemicals – especially of very similar substances – should be considered in threshold recommendations, because their effect can add up.

What are the main sources of our plasticizer intake?

Our main source through which we come in contact with plasticizers is our food. Almost all of our foods come in plastic films, containers or cans (whose coating almost always contains plasticizers).

Drinking water is another potential source of plasticizers, but it largely depends on the container we drink from. Plastic-free drinking bottles are a great way to make sure we don’t unnecessarily increase our intake of harmful chemicals through our drinking water.

Another way we absorb plasticizers is through the air we breathe. Especially in closed rooms plasticizers volatilize from floor coverings, wallpaper or wall paints and accumulate in the room air

Plasticizers also regularly make their way into the human body via skin contact. Phthalates, for example, are widely used (and very easily soluble) in thermal paper, which is used for receipts, tickets, invoices, etc.

But they are also included in many cosmetic products, which are directly applied to the skin.

How strongly are we contaminated with plasticizers?

Germany’s Federal Environment Agency monitors in regular studies the contamination of

- Virtually all analyzed urine samples contained degradation products of plasticizers – meaning that all children and adults are contaminated with phthalates

- These results are consistent with similar studies from other developed countries – so plasticizer contamination is not a national problem

- Children (especially toddlers) are often stronger contaminated than adolescents or adults – probably because children take more (plastic) objects in their mouths

- For some of the children, the level of contamination was so high that damage to their health could no longer be safely ruled out

- Since the

1990s , exposure to some phthalates (e.g., DEHP) has decreased, while exposure to substitute phthalates (e.g., DINP) has multiplied - In addition to the plasticizers analyzed in the study, there are many other (unexamined) plasticizers with a similar effect, which increase the health risk

Bisphenols – BPA and other hormonal substances

Bisphenol-A (often abbreviated as BPA) is often referred to as a plasticizer, but BPA is in fact not actually a plasticizer. However, it acts as an antioxidant for plasticizers and is therefore often added to plastics that also contain plasticizers.

Bisphenols (including BPA) are so-called endocrine disruptors – also known as environmental hormones. Because they are so similar to the human hormone estrogen, they damage our health in a variety of ways, as reported by the German Society of Endocrinology.

These hormone-like substances throw our finely balanced hormone system off balance, with many undesirable consequences. Infertility, hormone-dependent tumors, obesity, diabetes and developmental disorders in children are just some of them.

Which products contain BPA?

Since the 1950s, BPA has been the basic chemical building block of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, which are still widely-used. Drinking bottles – especially for babies – were made from polycarbonates for the longest time.

Although BPA has been banned in baby bottles since 2011 across the EU (and a year later in the US), it is still found in many other everyday items. Just in case you might wonder: yes, it is also still allowed in all bottles that are not specifically made for babies.

Virtually all PVC products contain it, thermal papers (e.g. receipts in the grocery store), plastic containers, inner coatings of cans, plastic dishes, toys, cosmetics and much more.

What about “BPA-free” alternatives?

BPA is on the list of “substances of very high concern” of the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) because of its reproductive-toxic effects on humans. Since January 2018, its harmful hormonal effects on animals and the environment have been added to this list.

The use of BPA in

Nevertheless, there is an enormous amount of products in which BPA is still used and where no regulations apply. With 3.8 million metric tonnes worldwide, BPA remains one of the most widely produced chemicals.

So in order to be able to continue selling their products – and because BPA got a bad image in public – the industry is looking for substitutes.

“BPA-free” is by no means harmless

Alternatives to bisphenol-A were found quickly, since its chemical cousins bisphenol-S (BPS), bisphenol-F (BPF) or fluorene-9-diphenol (BHPF) were already available. So technically, it is indeed correct to label these products as “BPA-free”.

But there’s a catch with these substitutes:

These substances are chemically very similar to BPA and therefore fulfill the same purpose. But while there are years of research and study data available for BPA, much less is known about the effects on health and the environment of those substitutes.

In cell experiments, however, they show comparable harmful effects as BPA. Some studies suggest an even more harmful effect, as Japanese and Chinese researchers recently published in the world’s most renowned science journal “Nature”.

So where does this leave us?

Well, the main problem with BPA is its hormonal effect – especially its similarity to the human hormone estrogen. So we are not really interested in “BPA-free” products if they contain substitutes that have the same hormonal effect as BPA.

Instead, we are interested in products that are free of so-called “estrogen-active” (EA) substances. This is the only way to avoid replacing one hormonally active substance with another and ultimately not changing anything about the original problem.

BPA substitutes are equally estrogen-active

Following this line of reasoning, a group of researchers in the US conducted a large-scale study back in 2011 to find out which commercial plastic products release hormonally active substances.

Over a period of three years, the researchers examined 455 plastic products that come into contact with food – including drinking bottles, food containers, bags, plastic wrappings, packaging and many more.

The selected products consisted of all commonly available types of plastic, including polycarbonate (PC), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP) and polystyrene (PS). Of all these plastics,

The test products were subjected to common stress situations, mainly UV light, microwave radiation, and moist heat. The researchers were interested in whether the substances that leached from the plastic had an estrogen-active effect – just like BPA does.

The conclusion of the study:

All tested “BPA-free” plastics had a verifiable estrogenic effect – in some cases the hormonal effect of the BPA substitutes was even stronger than that of BPA itself.

The BPA-free plastic “Tritan” is also hormone-active

The plastic Tritan has been manufactured and sold since 2007 by the US company Eastman Chemicals as a BPA-free alternative for the discredited (BPA-containing) polycarbonate.

Many bottles and food containers (often from well-known brands) are made of this plastic – and most of them advertise their products proudly as “BPA-free”.

The thing is: many studies show that Tritan (or the BPA substitutes used in the material) have at least as much of a hormonal effect as BPA.

Although Eastman Chemicals filed a lawsuit against the first company (CertiChem) that reported these findings could not prevent the facts from coming to light.

Dr. Thomas-Benjamin Seiler from RWTH Aachen University, Germany comments on the results of the team of international researchers:

“It is alarming that high BHPF values were found in the plastic Tritan, which is increasingly being used for children’s drinking containers and advertised as BPA- and phthalate-free.”

In short, even Tritan does not change the fact – but rather confirms that – substitutes for BPA are by no means less problematic than BPA itself.

How can I tell whether a plastic product contains harmful substances?

Unfortunately, in most countries, manufacturers are not required to list plastic additives as ingredients on the product or its packaging, so you cannot easily identify them.

Also, you can’t see, smell or feel plasticizers and other harmful substances. When it comes to soft plastic products, it is always worth investigating what they are made of. For instance, soft PVC always contains plasticizers, but it cannot be easily distinguished from silicone, which does not require any plasticizers.

According to the European Chemicals Act REACH, every consumer in the EU has the right to be informed by the manufacturer about potentially harmful chemicals. They have to tell you within 45 days free of charge if the product contains hazardous substances.

While that’s good to know, it does not really help if you’re in the store and unsure whether a plastic product contains any noxious chemicals or not.

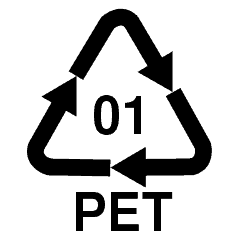

What might help is a look at the recycling code, often found at the bottom of the

For plastics, there are 7 different categories that look like this (this example shows the code for the plastic type PET):

The numbers and abbreviations stand for the following types of plastic:

- 01: Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) – best avoided (we’ll get to the “why” in a moment)

- 02: Polyethylene high density (PE-HD)

- 03: Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) – avoid like the plague, highly damaging to health and the environment!

- 04: Polyethylene low density (PE-LD)

- 05: polypropylene (PP)

- 06: Polystyrene (PS) – also known as Styrofoam – often contains very toxic additives – so avoid it whenever possible

- 07: Other (O) – this “miscellaneous” group includes the BPA-containing polycarbonate (PC) – best avoided

To put it simply, stick to the following rule of thumb: the only reasonably harmless plastics are PE and PP – code 02, 04 and 05.

While this is not an absolute guarantee, these plastics can be manufactured essentially without plasticizers or other toxic additives.

Are PET bottles unhealthy?

PET bottles neither contain unhealthy plasticizers nor bisphenol-A. Does that mean they are harmless?

You’ve probably noticed that water from PET plastic bottles sometimes tastes slightly sweet – especially after prolonged exposure to direct sunlight or heat. This is because PET releases acetaldehyde into the water over time.

Acetaldehyde has been shown to be harmful to health and may, among other things, damage the heart and lead to cirrhosis. Incidentally, it is also the degradation product of (drinking) alcohol and mainly responsible for the hangover on the next day.

It is true that it occurs naturally in very small quantities in fruits or cheese. And it is also true that there are legal thresholds in many countries as to how much acetaldehyde is allowed to leach from PET bottles into the beverage. But does this make the whole thing harmless and healthy?

Sterilization of PET bottles as potential health hazard

Since PET bottles cannot be sterilized with heat before filling – unlike glass bottles – a process called cold sterilization is used which involves the chemical DMDC.

Although this highly toxic substance is completely degraded within a short time within the bottle, the process produces O-methyl carbamate as a by-product, which has been shown to cause cancer in rats. That’s why it is on the list of cancer-causing substances of California.

Potential hormonal influence

The aforementioned US study had already demonstrated a hormonal effect of PET plastic products, even if PET does not contain BPA.

Researchers at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, have also repeatedly detected hormonally active substances in PET bottles.

However, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment does not agree with the results of the Frankfurt researchers and sees no need to recommend to consumers a switch from PET bottles to glass bottles.

Other toxic substances leach from PET

This interview (in

However, especially the last, harmless-sounding paragraph is a ripsnorter:

“Other substances such as ethylene glycol, terephthalic acid or antimony can leach into the mineral water in harmless quantities.”

Ok, so what are these “other substances” exactly?

Ethylene glycol is an alcohol and is highly toxic to humans – the dose for life-threatening poisoning in humans is 100 ml. The effect is quite similar to that of methanol poisoning.

Terephthalic acid is slightly toxic, can irritate the skin, eyes and respiratory tract and, at high doses with rats, led to bladder stones or their death.

Antimony is a metal that is highly toxic – probably the most dangerous of the three substances.

The question then becomes: Do we really want to ingest those chemicals regularly – even if only in small “harmless” quantities?

That is for each of us to decide. For most people, this is a no-brainer – especially since there are plenty of healthy and sustainable alternatives to PET bottles.

9 simple tips on how to protect yourself from harmful substances

On the one hand, the best thing would be to completely avoid using plastics that could contain harmful substances wherever possible. Of course, this is not very practical in our plastic society.

However, with the following tips, you can make a steady contribution to protecting your health and the environment:

- Avoid PVC at all costs – this is one of the most damaging plastics in terms of health and ecology. Similarly, try to avoid polyurethane (PU), polystyrene (PS) and polycarbonate (PC)as much as possible as they almost always contain toxic additives.

- If it has to be plastic, stick to polyethylene (PE) or polypropylene (PP). These are considered safe since they can be made without harmful additives.

- Do not fall for “BPA-free” products – that’s deceptive labeling. As you already know by now, almost all BPA substitutes are just as harmful.

- Avoid typical sources of harmful additives: tin cans (internal coating often contains BPA), disposable plastic bottles, etc. Instead, use glass or stainless steel products.

- Replace disposable plastic products such as cutlery, cups, mugs, containers, bags etc. with reusable and harmless alternatives such as glass, stainless steel, ceramics, cloth, etc.

- Avoid contact with thermal paper (receipts, tickets, etc.), which almost always contains BPA.

- If unavoidable, then dispose of the thermal paper via the residual waste, instead of the paper waste. That way you prevent BPA containing paper from being recycled and reused as printer or toilet paper.

- If you are not sure whether a product may contain harmful substances, you can use the smartphone app “scan4chem” provided by the Federal Environmental Agency. Unfortunately, this does not show you the ingredients directly, but it makes the request to the manufacturer easier.

- Avoid unnecessary plastic packaging when shopping. Loose fruit, vegetables, etc. do not have to be packed separately in a plastic bag. Bring your own, reusable carrying bag.

Conclusion

We live in a plastic world, that’s beyond a doubt. Each of us comes in contact with a wide variety of plastics on a daily basis

Through our food, skin and the air we breathe, we absorb a variety of chemical substances and additives that evaporate from the plastic products that we use and surround us.

We currently base our behavior on the assumption that this regular intake of a mix of chemicals – many of which have been proven to be harmful in cell and animal studies – will not have any long-term effects on our health.

In doing so, we rely on threshold values which are allegedly harmless (“TDI – tolerable daily intake”). However, these thresholds are not scientifically proven or in any way absolutely reliable values - but rather a well-intentioned estimate.

Furthermore, there is virtually no data on the effects of the interaction of a mixture of different substances which all of us are exposed to. Even those who suggest those threshold values for individual substances acknowledge this fact.

Yes, it is true that there is no clear evidence as to whether, when and what mix of chemicals might cause exactly which problems or diseases in humans.

But: Is it not better to err on the side of caution when in doubt?

If you do not want to put your health at unnecessary risk, then try to steer clear of the plastics mentioned in this article (which are proven to contain hazardous substances).

By becoming more aware as to which plastic products you can avoid or substitute with sustainable alternatives, you are doing something good not only for your health but also for your environment.

If it has to be plastic (does it really?), then try to stick to those types that we have recommended to you as relatively harmless.

You Might Also Like…

- Is Fast Food Bad for the Environment? (& What You Can Do)

- Is Fabric Softener Bad for the Environment? (+5 Eco-Friendly Options)

- Is Fuel Dumping Bad for the Environment? (& How Often It Happens)

- Is Electricity Generation Bad for the Environment? (What You Should Know)

- Is Dry Cleaning Bad for the Environment? (4 Surprising Facts)

- Is Diamond Mining Bad for the Environment? (Important Facts)

- Is DEET Bad for the Environment? 4 Effects (You Should Know)

- Is Cat Litter Bad for the Environment? (5 Common Questions)

- Is Burning Cardboard Bad for the Environment? (6 Facts)

- Is Burning Paper Bad for the Environment? (6 Surprising Facts)

- Is Burning Leaves Bad for the Environment? (7 Quick Facts)

- 4 Natural Cleaners for Quartz Countertops

- 6 Eco-Friendly Acrylic Paint Brands (For Sustainable Artists)

- 5 Eco-friendly Alternatives to Acrylic Paint (& How to Make Them)

- Is Acrylic Paint Bad for the Environment? (7 Quick Facts)

- Is Acrylic Yarn Bad for the Environment? 8 Crucial Facts

- Is Acrylic Bad for the Environment? (8 Quick Facts)

- Is Aluminum Foil Bad for the Environment? 7 Quick Facts

- Is Bleach Bad for the Environment? 6 Crucial Facts

- Is Lithium Mining Bad for the Environment? 6 Crucial Facts